Automating FPL with Machine Learning and MPC - Part 1: Machine Learning

I like football. I watch Everton disappoint me every week and mainly hatewatch Liverpool as well. But I can never be bothered with fantasy football. I have no interest in watching Brentford v Fulham; or checking whether Ben Gannon-Doak’s knee injury is worth him going on my bench or substituting for someone else. I don’t care to check whether the xG overperformance of Strand-Larsen is worth his discounted price compared to Chris Wood; and I definitely can’t be bothered to check this every week for 38 weeks. Excluding double game weeks, or the festive period, or if we decide to put a world cup in the middle of winter or whatever. But what I lack in attention span, I make up for with short term obsession; so I decided it would be an interesting project to try and get a computer to do all this for me instead.

A Discussion on Data

The most painful part of the project was getting the data. I argued a lot with ChatGPT about the best way to scrape all the stats from FBref, and this got really complex having to pretend I wasn’t a bot, and then deciding which stats were worth scraping, which were revelant (progressive carries?!) and which were actually worth using up precious space. Whilst I enjoy the more mathematical side of football, there really is some nuance in deciding if a statistic is really relevant; or as I like to think of it, predictive. Knowing the goal probability of a given shot (xG) is really powerful, and then being able to condition that probability on factors like keeper position and number of defenders in the way (xGOT) as well gives an idea of the quality of a given action. But knowing the amount of touches Everton had in the opposition penalty area the first half against Leeds (that would be zero) merely confirms my eyes telling me they were garbage. It doesn’t allow us to reproduce the actions, and from that evaluate how likely the match outcome was to happen. A better metric would be the probability of scoring from getting to these areas (or expected threat, xT, which would also have been near zero).

The overstatification of the Premier League is becoming more apparent, and we have shifted from subjective garbage, like Michael Owen speculating “the team who scores more usually wins…” to quantitivate, but irrelevant information, like Darren Fletcher telling us Man City have had the most corners in the Premier League this year. Brilliant value add. There’s a really good introduction to xG as a predictive stat in this book, and then a great discussion how it can actually be used in practise here, even if it’s about the most insufferable club in the world.

Anyway, I spent a lot of time trying to sort this, until I discovered that someone has pulled all the FPL data, and with that a lot of stats from the Premier League using the API each week. I was glad I wasted all my time when I could have used the GitHub repo here, so I ended up using it anyway.

Using Machine Learning

So now we have the data, let’s see if my PhD research is any use, and see if we can predict the future. The repo contains all the players in each gameweek in a given season, with relevant years being 2021/22 onwards (because of the integration of predictive stats). Each week contains stats on:

- Minutes and Starts

- Classic Stats like: Goals, Assists, Clean Sheets, Goals Conceded, Own Goals, Penalties Missed/Scored, Red/Yellow Cards etc.

- Expectations: xG, xA, xGI, xGC

- FPL Proprietary Stats: Threat, Influence, Creativity, ICT Index; and Bonus Points.

These are then integrated alongside the Expected Points (xP) for each gameweek; where we look more at the predictive side of the game, which hopefully over the course of the season would even itself out, instead of getting lucky at Chris Wood outperforming his xG each week.

The Predictive Model

The philosophy behind the model is a number of points a player will score is a function of their form and the team matchup. For example, a good attacking player is more likely to score against a poor, and hence score points, than against the great wall of James Tarkowski and Jarrad Branthwaite; but conversely those two beasts are more likely to be scoring when facing a toothless attacker. The PL API has a reasonable metric for replicating the strength of given team’s home and away attack and defence strength (as statistically, there is a home advantage of something like 7%), and we were able to utilise this to train an interesting ML model.

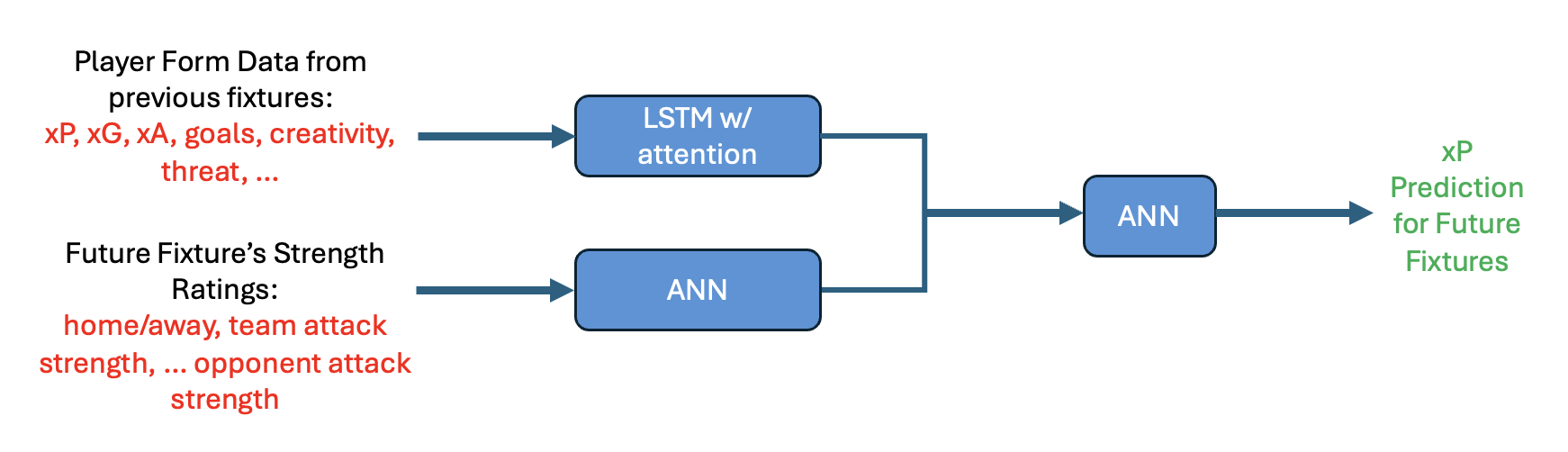

I settled on using a bi-input LSTM/MLP model. An Multilayer Perceptron or Artificial or Feedforward Neural Network is standard sequential neural net. It’s a load of linear layers that use an activation function to add non-linearity which is then able to capture complex relationships between input and output variables (like how expected points and a team’s strength are related!). An LSTM is a variant of Recurrent Neural Network. It is good because it can work better with sequential data, like a how players stats for previous matches might impact their expected points, whilst being able to store previous hidden states, to act as ‘memory’. They use magic ‘gates’ to pass data through, which use different activation functions to prevent exploding/vanishing gradients during loss calculations.

This LSTM, however, not only has its magic hidden, input and forget gates, but also utilises an attention mechanism, to ‘enhance its ability to learn sequential dependencies’. Attention is the backbone of large language models and is essentially the calculation that figures out to say ‘you’re welcome’ when you thank ChatGPT for its help. It relates the importance of different datapoints in a sequence, like how relevant is a players xG in the previous game to one 5 games ago to predicting their xP in the upcoming fixture. Or how relevant the word relevant is in this sentence, to predict that the next word is apple.

Either way, this whole cell then takes in each players previous 5 gameweek form, taking in their prior performance in stats, and transforms this to an ‘embedded latent vector’. I used an attention mechanism as my initial training of the model was giving terrible results, and this was the first thing Gemini, Claude and ChatGPT suggested doing as it would ‘improve my model’. A schematic of the model structure is shown below:

In actual fact, trying to train on a dataset with loads of outliers on the MSE loss function doesn’t give great results. It’s actually much better to use the MAE or HuberLoss (adapts between MSE and MAE), because the xP is quite erratic. Perhaps I should have tried to visualise this beforehand and saved myself all this time, but this can be the first learning curve of the project.

I chose 5 previous games because it was a nice round number, and as I started the project about 4 days before the FPL deadline, so I didn’t have time to mess with it. The MLP takes the next 3 teams the player is going to face, and their ‘strength ratings’, relative to the original team. The combination of both these input heads, creates a final embedded vector that is then passed through an MLP, to predict the xP for the players’ next 3 games. The model predicts 3 future games as a trade-off between taking a greedy strategy (TBD in part 2!), whilst also maintaining a fairly accurate predictive model. Again, I would try and tune this if I were to rebuild this model. This was also simpler than predicting the next gameweek stats and iteratively predicting future gameweeks, which would make my controller worse. More on this later.

I ended up training these models with the HuberLoss function, with 2 input MLP layers, 2 LSTM layers, with each layer containing 128 neurons. I trained the model on all players within the 2021-22, 2022-23, 2023-24 seasons. I did enjoy the model breaking at GW7 in 2022-23 (once in a generation moment as to why). My test set was the most recent 2024-25 season. As we are utilising temporal data, it’s important to filter the data like this to avoid data-leakage and making the model crap. This gave me a loss of about 0.12 across the train and test set, which although isn’t perfect is probably fine, because firstly, I didn’t really have the time to improve this or scrape more / better quality data. Secondly, although an MPC is only as good as your model, this is in essence a preferential learning problem. My model might predict Erling Haaland to get 6.87 xP this week, and he might end up with 8.35 xP instead; but as long as the model knew Haaland is a better pick than Jack Harrison, it isn’t that deep. So to quote one of my undergrad lecturers, here we found that ‘if it works, it’s good enough’.

One of my biggest hates when I read papers that use ‘ML’ is the lack of uncertainty quantification in the models that are used. Loads of research treats these models as magic that will predict everything with ease, and without actually understanding their limitations (which like the predictive stats, is important to know). Training a neural network is so stochastic what is to stop it predicting that Harrison Armstrong is going to get 10.47 points this weekend, there’s no guarantees that your loss is in any way correct. But understanding how confident your model is in that prediction is one way to be certain about your uncertainty.

I was at a summer school recently, where one talk was attempting to bridge the gap between statistics and ML communities, especially the theory grounding uncertainty quantification. If there’s one thing I took away, was his inner hatred of ensembling as a method of UQ. “It’s not Bayesian in the slightest”, “it’s not acceptable within safety critical applications at all”. This application is probably not too safety critical, and ensembles are quite an easy way to get a value for uncertainty in a prediction. After all, what would be a reasonable ‘prior’ to assume on weights to predict football matches. Either way, DeepMind’s weather models do it, and if it’s good enough for them, it is after all ‘better than nothing’, so Jeremias if by chance you are reading this. Sorry. Did like the talk though was interesting. And it figured out there was a massive variance when the single model was trying to pick Gvardiol as captain every week.

I ended up training 10 models in parallel to predict the xP for each player, which allowed for more consistency in predictions, and reduces downside risk. If we take two players for example: Erling Haaland, gets predicted xPs by our ensemble of 8.35, 7.92, 8.12, 9.14, etc, which gives you a mean of about 8 something and a standard deviation of around 1. I am not sure because I made them up.

But then, say our model wants to predict Michael Keane’s xP, which the ensemble works out as 1.27 (realistic, probably gave away a penalty), 14.37 (he probably scored a worldie), 3.46, 0.45, etc.

If our singular model just predicted that MK would get 14.37 xP compared to Haaland’s 7.92, our controller would then take the Keggerman, which sorry Michael, we probably wouldn’t want to do, and gives the intuition behind ensembling multiple models.

Potential Improvements

The first issue with the model lies within the data itself. Lots of the features the model relies on for prediction are proprietary, such as team strength ratings, threat, creativity, ICT index, etc. Although there is a rough indication what they mean, actually understanding where these values come from could allow the model to be adjusted to enhance predictive accuracy, or built in a better way, as these probably aren’t optimised to predict their points, more just a way to gauge a player or team’s ability.

As these stats are proprietary to the Premier League, there is no clear of getting a players creativity in a different league. For example, trying to figure out the threat rating Gyokeres should be assigned is no easy feat, we can either ignore players who have joined the league, and potentially miss out on loads of points, like with Haaland, or try and find a proxy.

To try and incorporate players who are new to the Premier League, firstly I scraped all the players who had joined the Premier League since 2020 from all major leagues. From this, I found a multiplier that corresponds to stats in one league to the next, which was some horrible distribution. For example, to translate xG/90 from the Portuguese League to the Premier League, you multiply by around 0.78, meaning a certain goal in the Premier League might only be scored 3/4 times in Portugal. Of course, this is a crude approximation, but I’d argue this is better than assuming all leagues are the same standard (they’re not).

After applying these factors, I also built a standard 3 layer Neural Network to serve as a proxy to predict a players creativity, threat and ICT index, given various stats about their xG, xGOT, xA, as well as their actual goals and assists. This essentially allowed us to create a proxy for Viktor Gyokeres’s form had he played in the Premier League, going into this season. However, had I had more time, I’d probably take a more probabilistic approach, and using Monte-Carlo simulations, could have given a better estimate of this, rather than directly translating each player using average values.

Developing my own player ratings and predictive metrics could be one route to improve the predictive accuracy, however this would be fundamentally limited by data. There are concepts, such as conditional expected threat, where the idea is to take a player such as Illiman Ndiaye, and work out how many goals would he assist, if he was to be playing the ball through to Haaland, rather than Dominic Calvert-Lewin, who is usually too busy tripping over his high heels to put the ball in the goal. However, even with all of the scraping in the world, there just isn’t enough public access to high quality data to build a model like this (collab @opta?).

I think this just about concludes the first part into what could be 2, could be a 3 part series on how I am trying to lose mates using ML and Fantasy Football. It might have been waffley, and in the future I might look back and think it was all badly written and useless, but lets see how well the model does this year. The next parts, I’ll talk about applying this model within a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) framework to firstly build a static ‘optimised’ FPL team, and then how I developed it to use a full receding horizon control strategy, to dynamically make decisions on starting XI, captains and transfers for a full season.

A big shoutout to Vaastav on the GitHub repo, it’s been a fantastic help with this project. Also big thanks to Iwan Pavord, who’s one of my colleagues in our research group. He somewhat inspired me to look into this when he first joined our group, and he did something cool about trying to track your own minileagues between mates. He’s also trying to do a similar thing but using Reinforcement Learning instead, which is way too much compute/building my own environment to bother getting involved with. I’ll leave a link to his project if he writes it up.

Hope you have enjoyed reading, make sure to like, subscribe, leave a comment below and I will see you on the next one.

Don’t go changin’